Recombinant protein production is a sequence of upstream and downstream operations that converts a validated DNA construct into a biochemically characterized, concentrated protein reagent.

Recombinant protein production is a sequence of upstream and downstream operations that converts a validated DNA construct into a biochemically characterized, concentrated protein reagent.

▌A. Construct verification and expression system selection

The technical workflow begins with a verified expression construct — the exact DNA sequence encoding the polypeptide to be produced (including any cloning scars, linkers and affinity tags). Sequence confirmation by Sanger or next-generation sequencing is treated as a basic technical gate: an incorrect ORF, frameshift, or unwanted mutation will propagate failures downstream.

Selection of the expression system is a technical choice driven by the protein’s biochemical requirements (size, disulfide bonds, required post-translational modifications), the intended analytical uses, and throughput targets. Laboratories and service providers routinely choose among bacterial (Escherichia coli), yeast, insect (baculovirus), mammalian (transient or stable CHO/HEK293 cells) and cell-free systems; each system presents a distinct technical profile for translation capacity, folding environment and possible modifications. Practical technical literature and company resource pages present these systems side-by-side to inform the choice.

Common technical expedients at this stage are the inclusion of short affinity or solubility tags on the expressed polypeptide (for capture and analytical ease), a choice of signal peptides for secreted expression when needed, and a plan for verifying expression (small-scale test expressions and SDS-PAGE or Western blot checks). These simple checks keep the downstream workflow efficient.

▌B. Expression and harvest (upstream)

Expression is executed at the appropriate scale for the project: milligram-scale bench expressions for structural or functional assays, or larger cultures when more material is required. Technically, expression runs fall into two groups: cell-based and cell-free. Cell-based workflows proceed through inoculum preparation, controlled cultivation (shake flask, bench fermenter, or suspension culture), induction or transfection, and expression incubation under controlled time/temperature conditions. Cell-free systems bypass cultivation and translate directly from template DNA/RNA in a lysate; they are increasingly used for rapid, small-scale synthesis of “difficult” proteins or for rapid isotope-labelled material.

When the expression run is complete the technical harvest step depends on localization of the expressed product: secreted proteins are recovered from clarified culture supernatant, whereas intracellular products require cell disruption (mechanical or chemical) followed by clarification (centrifugation and filtration) to remove cell debris and nucleic acid-heavy fractions. Clarification is performed to produce a feedstock compatible with affinity capture media and chromatographic columns.

▌C. Capture, purification and analytical release (downstream)

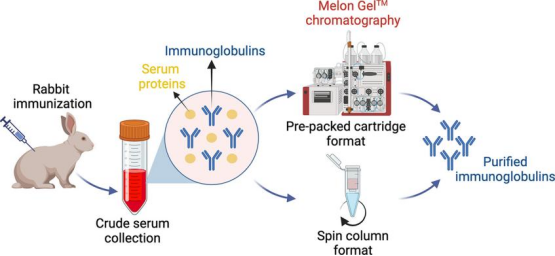

Downstream processing starts with a capture step whose technical aim is to remove the bulk of host contaminants while concentrating the target protein. Affinity capture has become the near-universal first step in many workflows because it is selective and fast: polyhistidine (His) tag capture on immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC), Strep-tag capture, GST capture, and antibody-based affinity resins are common technical choices. For secreted proteins that require native processing, or for proteins that cannot carry a tag, lectin or ion-exchange capture strategies may be used. Technical references and company protocols describe typical loading capacities and recommended buffer conditions for these capture resins.

Following capture, routine polishing steps remove remaining impurities and separate isoforms or aggregates. Standard polishing modalities include ion-exchange chromatography (IEX) to separate species by charge, hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) where surface hydrophobicity is a differentiator, and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to resolve monomeric species from aggregates. In practice a two- to three-step chromatographic train (capture → intermediate → polish) is frequently sufficient to reach research-grade purity. Buffer exchanges and concentration steps (e.g., tangential flow filtration or centrifugal concentrators) are standard technical operations to formulate the protein in the desired buffer and concentration range for storage and assays.

▌Analytical characterization and release

A minimal technical release profile is centered on identity, purity, integrity and homogeneity. These are checked with routine orthogonal methods:

• Identity: mass spectrometry (intact mass or peptide mapping) or immunoreactivity assays to confirm the molecular identity.

• Purity and integrity: SDS-PAGE (Coomassie or silver staining) and capillary electrophoresis or reversed-phase LC for detecting truncated species, degradation, or host-cell proteins.

• Homogeneity/aggregation state: analytical SEC and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to quantify oligomeric state and aggregate content.

• Endotoxin and microbial bioburden (for material intended for cell-based assays): Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assays and standard culture methods.

There is broad community guidance recommending a small, agreed set of minimal QC tests that are sufficient for most downstream research uses; these guidelines are commonly adopted by both academic and commercial providers as a technical minimum for reagent release.

▌Typical technical documentation delivered with a batch

From a service viewpoint, completed batches are accompanied by technical documentation that typically includes: the verified construct sequence, expression host and batch identifiers, a summary of the upstream conditions, chromatograms or resin usage logs, analytical data (SDS-PAGE images, MS summary, SEC profiles, concentration and yield), and storage/handling instructions. This package enables users to interpret experimental outcomes and, when necessary, to reproduce or rerun the process.

▌Storage, formulation and handling (technical notes)

The protein’s physical stability is governed by buffer composition, pH, ionic strength, and storage temperature. Common technical practices include adding stabilizing excipients (glycerol, sugars, reducing agents where appropriate), using low-binding containers for dilute samples, and aliquoting to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. For many routine research proteins, −80 °C long-term storage or −20 °C with 10–50% glycerol is standard; sera-compatible or cell-culture exposed proteins typically require special attention to endotoxin content and formulation compatibility.

▌Simple path to reproducibility and traceability

From a technical management standpoint, the three pillars that make recombinant protein workflows reproducible are:

(1) a validated sequence and clear construct map;

(2) pre-defined, documented upstream and downstream protocols with critical operating ranges for key steps; and

(3) a concise analytical release panel that verifies identity, purity and homogeneity.

These three items together create a robust technical ledger that enables both routine production and troubleshooting.